Author:

Green Steps

Short summary:

This article looks into the psychology of why we do not react to climate change with the urgency which is needed, and explains the neurology behind human fight and flight behavior. It conceives a learning platform which combines positive communication with an infrastructure of human motivation.

Imagine its 2021. Greta Thunberg, the young lady whom we watch in the media growing up like Harry Potter movie stars, speaks again in Davos. But this time, instead of telling the world’s leaders that they all failed to stop climate change, she proclaims: Behold, I have a solution.

She smiles and unveils a vision to save the planet and humanity.

What are we supposed to do if robots and algorithms take (most) of our jobs? For some it’s a blessing not having to work anymore; for others it is a curse. The real problem is though how to psychologically fill the void with meaning. It was neurologist Viktor Frankl who said that more and more people have the means to live but a life without meaning. People without a meaning tend to compensate their frustrations with more consumption and thereby contribute significantly to climate change. We need societies which are thriving with purpose to cool our home.

I have predicted on different occasions that both secondary and tertiary labor markets will follow a similar trajectory like agriculture. Employment as total of the labor market will tumble to below 2%. I have also predicted that craftsmanship and self-reliance agriculture have the potential to absorb much of the unemployment if we gradually prepare our youth for such a future instead of conditioning our children into office work of whatever kind. This view is only shared by a few contemporaries because they can’t reconcile it with the modernity paradigm which disrespects manual work.

The question will be in future not only how to make a living, but how to survive in the most elementary sense without generating more heat. A cynical upside from a labor market perspective: humanity will soon be reduced substantially, and the problem might solve itself. The era of the Anthropocene implies that we target a 5˚Celsius temperature increase, which will lead eventually to the 6th mass extinction. Some people like Elon Musk prepare themselves and work on our species’ survival on Mars. I don’t say that’s wrong, but I would like to see the resources of his project used for a solution on planet Earth.

Nathaniel Rich writes in the New Yorker magazine gloomily that all this wouldn’t have been necessary. He claims that between 1979 and 1989 (American) scientists had understood the impact of fossil fuel on the planet and had succeeded to convey these findings to decision making politicians. America was then humanity’s cutting edge and American humanity failed.

Illuminated British author Aldous Huxley wrote already in 1962, only a year before his death, the essay The Politics of Ecology. More than 10 years before German-British economist E.F. Schumacher published Small is Beautiful, Huxley boils down the complexities of our species in only a few pages and puts all the blame on greed and fear – not on fossil fuels. If you want to understand the cause of climate change and global warming, this is one of the most authoritative (and shortest) sources.

Journalist Georg Diez asks in the German weekly Der Spiegel in reply to Rich’s essay why the extinction of humanity stirs only little interest. His smartest answer is simply that a species’ biological extinction is a problem too complex to understand. Bill Mollison, the co-founder of permaculture, had made a remarkable comment, when he said: Though the problems of the world are increasingly complex, the solutions remain embarrassingly simple.

Discussing climate change should not be about explaining the scientific complexity of its causes but about putting forward a simple solution that people can work with.

So, why does humanity show only little interest in its own demise? A simple rule of communication answers this question as sound expert Julian Treasure explains in his brilliant TED talk how to speak so that people want to listen. Avoid the seven sins of speaking (gossip, judging, negativity, complaining, excuses, lying, dogmatism) and follow the four golden rules (Honesty, Authenticity, Integrity, Love - HAIL). In short, don’t be negative, but share a positive vision.

This insight is nothing new. Hailing has a great track record. Think for a second of the New Testament. Its four evangelists, Matthew, Mark, Luke and John do not deliver Hiob’s twitter, but an evangelical gospel, i.e. good news. The root of the word evangelist is classic Greek εθανγελιον | euangelion, which literally means to announce the good. In periods of despair, and only then, people listen to the good, the true and the beautiful. Otherwise they play Warcraft, watch Poltergeist or read the FT.

What we lack is a positive narrative of our own collective future - the dark side of humanity has already been described in all clarity by Aldous Huxley and many others. We know all too well that there is something utterly destructive in our nature and that there is no point to either explain the environmental consequences in all scientific detail or the regression of civilization ruled by a power hungry elite. What we need is a shiny storyline which appeals to our mystic subconscious, guiding us like a lantern out of our cave.

Culture critic and educator Neil Postman was absolutely right, when he compared the present machine age with the past of the dark Medieval Ages. We need a miraculous myth which peels off the apathy and ignorance that has settled on our minds, skins and in our hearts. We need a myth that changes gear from negative thinking to positive action. Don’t despair – do something! Jasmine Lomax posted recently on LinkedIn. Yes! But what?

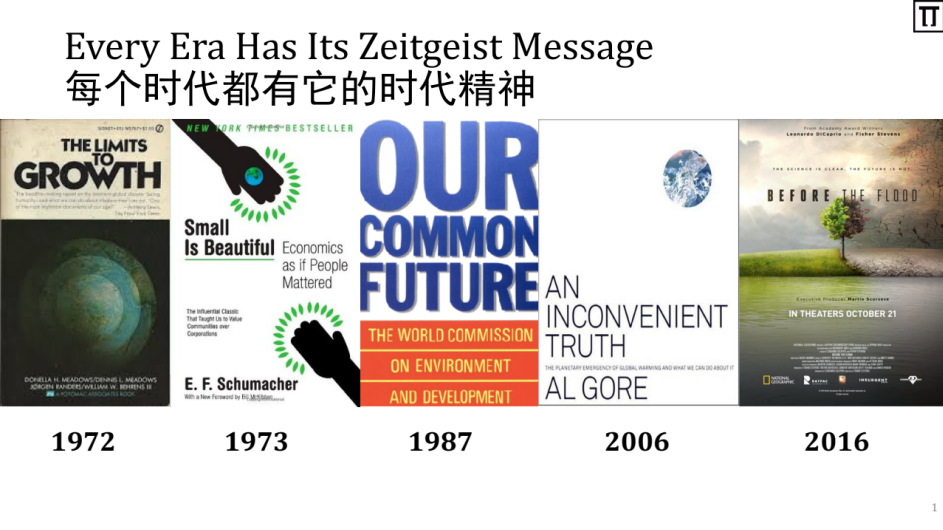

Every Era has its Zeitgeist Message

Some people are trying hard since WWII to set best practices to follow. There are writers and film makers like Leopold Kohr (The Breakdown of Nations, 1957), his student E.F. Schumacher (Small is Beautiful, 1973), Paul Hawken (Blessed Unrest, 2007), Colin Beavan (No Impact Man, 2009), Shelly Lee Davis (Planeat, 2010), Lee Fulkerson (Forks over Knives, 2011), Helena Norberg-Hodge (The Economics of Happiness, 2011), Nils Aguilar (Voices of Transition, 2012), Cyril Dion (Tomorrow, 2015), or Kurt Langbein (Time for Utopia, 2018) who show in their work how we can turn this ship around.

Their work features concrete solutions and taller than life individuals who have contributed in different disciplines over the last few decades to the shape of a yet fuzzy solution. There is the biochemist and nutrition scientist Thomas C. Campbell finding evidence that animal based protein causes cancer; or cardiologist Cladwell B. Esselstyn who showed in long term studies that a plant based diet can stop and even heal coronary and cardiovascular disease, the #1 cause of death in modern societies. There are activists like the founder of the transition network Rob Hopkins who understands like few others the force of a positive story and the power of local communities to bring such a story to life.

.png)

In reviewing some of the “transformation” work produced since WWII, I make two important observations. Firstly, early pieces like The Breakdown of Nations, The Politics of Ecology, The Limits to Growth or Small is Beautiful, focused on abstract concepts and ideas derived from economics, sociology and political science. The mushrooming – mostly – film work of the visual 21st century can though be broken down in two groups: the first continues to focus on concepts, the second tells stories which are pegged to a person.

The second observation is related to how increasingly difficult it has become to craft a positive scenario for our common future in spite of the overwhelming scientific evidence that we have one or two decades left before shit literally hits the cosmic fan. It is exactly under this pressure of moving into a no-escape bottle neck that messages become more focused and less abstract. A big threat is thus also a big opportunity. Without other solutions in sight, a single positive vision is more likely to be accepted by a substantial number of people.

.png)

The so-called happiest man on the planet, biochemist and Buddhist monk Matthieu Ricard, once said that although we want to avoid suffering, it seems we are running somewhat towards it. And that can also come from some kind of confusions. One of the most common ones is happiness and pleasure. But if you look at the characteristics of those two, pleasure is contingent upon time, upon its object, upon the place. It is something that -- changes of nature. Beautiful chocolate cake: first serving is delicious, second one not so much, then we feel disgust.

Another truth is though that we have conceived, designed, assembled and manufactured an infinite number of chocolate cakes and the consumer is never bored or disgusted. The consumer is in a processing loop of how to satisfy the next want which is generally created by the sensory stimulation of advertisement which correlates to an epidemic of deficient self-love. What we need to learn is how to sharpen the triple focus (inner, outer and other) as psychologist Daniel Goleman described the attention to the most sincere and urgent needs of the self, others and the environment.

Want and need are two different things, like pleasure and joy. A want is something superficial and short lived, a need is something deep and lasting. I might want a quick fuck, but I actually need a healthy relationship. I might want an industrial chocolate bar, but I actually need a healthy, self-cooked and balanced meal. I might want a sports car, but I actually need a decent bike to exercise purposefully. The interesting observation is that mostly what we need is good for others and the planet too, while what we want mostly destroys us and our environment. Needs originate in the soul, wants in the ego.

The Art of Storytelling

.png)

.png)

To most of us this is nothing new, but still it’s so difficult to change from want to need. Cognitive psychologist Daniel Levitin explains why: Prior to the invention of writing, our ancestors had to rely on memory, sketches, or music to encode and preserve important information. Memory is fallible, of course, but not because of storage limitations so much as retrieval limitations. Some neuroscientists believe that nearly every conscious experience is stored somewhere in your brain; the hard part is finding it and pulling it out again. Sometimes the information that comes out is incomplete, distorted, or misleading. Vivid stories that address a very limited and unlikely set of circumstances often pop to mind and overwhelm statistical information based on a large number of observations that would be far more accurate in helping us to make sound decisions about medical treatments, or the trustworthiness of people in our social world.

In short: numbers suck, but stories rule, numbers confuse while stories enlighten. Our brains want the hero’s journey – a single story which actually shows us the light at the end of the tunnel - but media delivers horrifying statistics and dooms scenarios. Levitin continues to explain that our modes of thinking and decision making evolved over the tens of thousands of years that humans lived as hunter-gatherers. But instead of concluding that we need more and better stories to memorize things that matter – or maybe just one grand myth which clears the data jungle - he concludes that our genes haven’t fully caught up with the demands of modern civilization and continues to write a substantial book about how to overcome our evolutionary limitations

Disney’s 2016 smash hit animation movie Moana told us such a hero’s journey and grossed USD 645 million at the global box offices. A Hercules like demi-God takes the heart from the Goddess of Life (Te Titi) and turns her into the Goddess of Death (Te Ka) bringing draught, infertility and devastation to the people of Maui. It is Moana, daughter of a tribal chief, who trusts her intuition and defies tradition by bringing the forgotten ancestral skill of wayfinding back to life. She heads out into the oceans to restore the heart of Te Titi and her courage is eventually rewarded with the world being put back into balance.

Contemporary Education Paradigm & Parents’ Responsibility

Our competitive knowledge economies have installed education systems which gear our children as smallest units in such economies towards competition. It is though competition which increases consumption and loneliness, while collaboration can not only resolve environmental, but also social problems. As parents we can put our offspring on track to develop a true sense of belonging if we repeatedly participate in clean up events, take them on long distance hikes or engage in communal living. We bond with our children and with strangers through a joint act of meaning, while we alienate ourselves from our children and from the planet if we continue to be tied to our screens and the satisfaction of our wants.

Most parents, I have realized, don’t really know what to do with their kids. They are in this constant battle of having to supervise and make competitive their offspring while wanting to enjoy their own often sparse time off. The nuclear family has turned into a mini gulag generating maximum GDP growth, because every product and every service has to be purchased by ever smaller family units. We support our economies at the expense of our children who have to pay the bill in less time with their parents and being completely brought off course from a fulfilling profession and life. Michael Ende’s dystopian novel Momo has become everyday reality.

This is why in particular in Shanghai cram schools and after school classes are flourishing in a way other industries can only dream of. Recent IPO’s of such privately held companies are evidence of an utterly sick development. We fail to see that what our children need is not more supervision, but only a bit of purpose and lots of community. If there is purpose, then leave the child alone as Tom Hodgkinson wrote in the must read The Idle Parent. Tell them where to go but let them go alone. The true problem is this: we don’t know anymore where to go. We have lost the skill of wayfinding.

400 years of capitalism has created a strange conflict of infinitely more material wealth at the expense of planet and people by focusing on profit and competition. Post-materialism will need all of us to maintain appropriate and fairly distributed material wealth in addition to a push for spiritual growth by focusing on purpose and collaboration. It is the responsibility of each parent to turn around this spaceship Earth by showing our children these, well, not really new, but lost coordinates. It doesn’t take politicians or corporate leaders for this. It a system transformation and takes self-leadership. Be a Moana and trust your intuition for wayfinding.

.png)

Wayfinding and System Blindness

Why do we not we not react to the 6th mass extinction? The story of Moana gives us a more complete answer than Spiegel journalist Georg Diez whom I quoted earlier saying that a species’ own biological extinction is a problem too complex to understand. Psychologist Daniel Goleman, known by many for his bestseller Emotional Intelligence, wrote in his last book about the Polynesian art of wayfinding, which is beautifully explained in the Disney animation: piloting a double-hulled canoe with only the lore in your head, traversing hundreds or thousands of miles from one island to another. Wayfinding, he writes, embodies system awareness at its height, reading subtle cues like the temperature or saltiness of seawater; flotsam and plant debris; the patterns of flight of seabirds; the warmth, speed, and direction of winds; variations in the swells of waves; and the rising and setting of stars at night. All that gets mapped against a mental model of the where islands are to be found, lore learned though native stories, chants and dances.

Ancient lore is the integral understanding of and ultimately surviving in an ecosystem, which is handed down from the elders to the next generation. As the world has industrialized, we have lost our local ecosystems and deal with a global ecosystem. We have lost our lore and are rendered blind to the system at large. Goleman elaborate furthers: Through human history, system awareness – detecting and mapping the patterns and order that lie hiding within the chaos of the natural world – has been propelled by this urgent survival imperative for native peoples to understand their local ecosystems. They must know what plants are toxic, which nourish or heal; where to get drinking water and where to gather herbs and find food; how to read the signs of seasonal change. […] Native lore has been a crucial part of our social evolution, the way cultures pass down their wisdom through the time. Primitive bands in early evolution would have thrived or died depending on their collective intelligence in reading the local ecosystem: to anticipate key moments for planting, harvesting, and the like – so the first calendars came into being. […] But as modernity has provided machines to take the place of such lore – compasses, navigational guides, and, eventually online maps – native people have joined everyone else in relying on them, forgetting their local lore, like wayfinding.

Goleman continues to give a neurological answer why we are not able to react properly to the 6th mass extinction. In addition to mismatches of our mental models and the systems they presume to map, there are even more profound predicaments: our perceptual and emotional systems are all but blind to them. The human brain was molded by what helped us and our forerunners survive in the wild, particularly in the Pleistocene geological epoch (roughly from 2 million years ago to about 12k years ago, when there was the rise of agriculture). We are finely tuned to a rustling in the leaves that may signal a stalking tiger. But we have no perceptual apparatus that can sense the thinning of the atmosphere’s ozone layer, nor the carcinogens in the particulates we breathe on a smoggy day. Both can eventually be fatal, but our brain has no direct radar for these threats.

Its not just perceptual mistuning. If our emotional circuitry (particularly the amygdala, the trigger point for the fight-or-flight response) perceives an immediate threat it will flood us with hormones like cortisol and adrenaline, which ready us to hit or run. But this does not happen if we hear of potential dangers that might emerge in years or centuries to come; the amygdala hardly blinks. The amygdala’s circuitry, concentrated in the middle of the brain, operates automatically, bottom-up. We rely on it to be on the alert for dangers and tell us what we need to pay urgent attention to. But our automatic circuitry, usually so reliable in guiding our attention, have no perceptual apparatus or emotional loading for systems and their dangers. They draw a blank.

At one time, the survival of human groups depended on ecological attunement. Today we have the luxury of living well using artificial aids. Or seem to have the luxury. For the same attitudes that have made us reliant on technology have lulled us into indifference to the state of the natural world – at our peril. So, to meet the challenges of impending (global) system collapse we need what amounts to a prosthesis of the mind.

Some scientists have already thought about such a prosthesis and have devised a measurement which indicates how close we are to a system collapse. Azeem Azhar, a London based entrepreneur, investor and publicist reminds the readers of his weekly newsletter of the CO2 levels in the atmosphere and the number of days until reaching the 450ppm threshold. The latest measurement (as of January 23): 413.14ppm; January, 2017: 406.13ppm; 25 years ago: 360ppm; 250 years ago, est: 250ppm. One could conceive such a measurement as a prosthesis of the mind. Albeit clear in its language, it harnesses fear and does not show what to do.

Green Steps ARK

The people at Green Steps, a Shanghai based environmental education startup have devised a prosthesis which motivates people to take small and gentle steps towards more empathy for the planet, others and the self. It functions like a railing people can hold on to learn what matters in the Anthropocene and its designers have made several basic assumptions which I want to outline here.

1. The human brain’s ability to change peaks before age 12 and decreases after that gradually with the increase of age. Simultaneously the effort one has to make to change habits and behaviors increases. It is therefore a safe assumption that the most impactful measure to tackle climate change relates to what children learn.

2. For much of human existence learning was connected to ecosystems and on how to relate with one another. It is only since the invention of language and the rise of Neolithic civilizations that humanity has shifted gradually towards learning, which is detached from the ecosystem, we live in. The scientific and in particular the industrial revolution have accelerated this process and put a focus on standardized STEM subjects. The result are national curricula across the globe which are similar in content and objective: train scientists and engineers for competitive knowledge economies.

3. Exponential climate change and exponential technological change requires a new focus. As citizens of a single home, we need to formalize and standardize our curricula on ecology and empathy. We need to give absolute freedom to our children to learn everything else. This is the paradigm of post-industrial and post-national education.

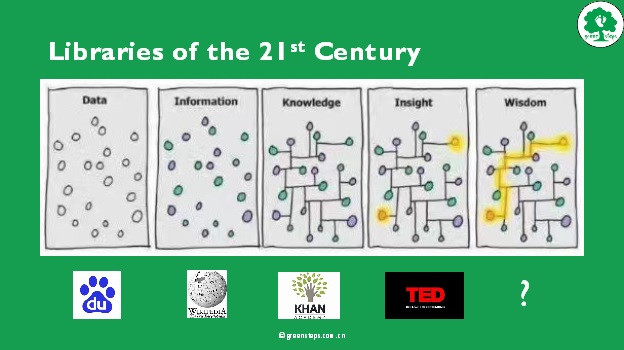

4. Culture critic Neil Postman said 30 years ago that the tie between information and action has been severed. Information comes indiscriminately, directed at no one in particular, disconnected from usefulness; we are glutted with information, drowning in information, have no control over it, don't know what to do with it. We therefore need a 21st century library which contains the information we need for our survival only.

5. Frederick Laloux wrote that every time humanity has shifted to a new stage of cultural evolution, it has invented a new way to collaborate, a new organizational model. The Green Steps ARK has been conceived as a Khan Academy for ecological intelligence which will be implemented in decentralized communities and supported by appropriate technology to scale impact. It will disrupt the existing organizational model of education and empowers everybody willing to qualify to become a teacher of the next generation.

6. A prosthesis for the mind only works when people are willing to use it. The Green Steps ARK is designed to make learning a community driven experience and uses the psychology of gamification to engage learners. As psychologist Adam Alter wrote: Tech isn’t morally good or bad until it’s wielded by the corporation that fashion it for mass consumption. We will wield tech for an evolutionary purpose: survival on planet Earth, our common home.

The Green Steps ARK does not explain the scientific complexity of climate change and its causes but puts forward a simple solution that people can work with and creates a positive vision of how post-industrial education can unfold human potential.

.png)