Author:

Bee-eater

Short summary:

The restoration of industrial landscapes to tap into the life-sustaining ecosystem services of water bodies constitutes a colossal challenge for local and regional governments. Place-based education is a pedagogical method which provides students real life opportunities of learning, helps communities to save cost and garner wider support for required climate adaptation projects. Combining formal education with ecosystem restoration is a realistic strategy to make necessary things happen.

The arrival of the Northern Lapwing (Vanellus vanellus) heralds not only in Neusiedler See National Park the beginning of spring. This migratory bird returns to Central and Eastern Europe starting in late February from his winter habitats in Southern Europe and Northern Africa. His iconic call (listen here!) and the dramatic air maneuvers for territorial protection (watch here!) reinforce the growing strength of the sun and tell us that Persephone, the goddess of vegetation, has emerged from the underworld.

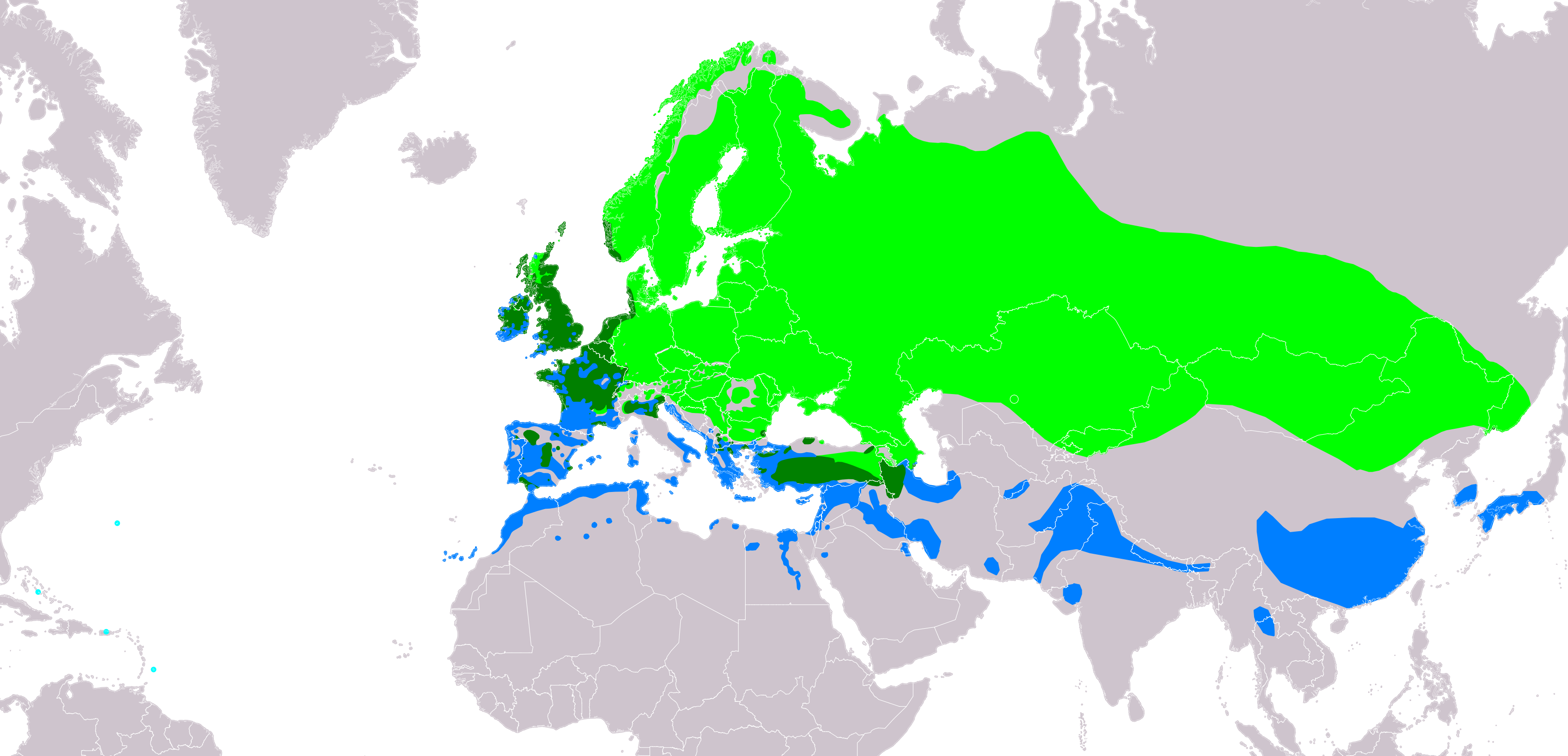

If you want to see and hear the Northern Lapwing in central Europe, you must nowadays travel to protected areas like Neusiedler See national park in the far east of Austria. What was once an ubiquitous sight and sound has become so rare, that IUCN has added the Northern Lapwing in 2015 to the red list of endangered species. Since the 1980s, changes and intensification in land management and changes in water management have led to an ongoing loss of habitat. Among other things, the conversion to winter cereals, increasing mechanization of agriculture, increased use of environmental chemicals and thus a decline in insects available as food, earlier mowing, a decline In extensive pasture management and a lack of spring flooding have played a role in this. Due to this progressive destruction of its habitats, populations have declined not only sharply in continental European countries like in Germany, Switzerland and Austria, but also the United Kingdom.

2024 September Floods in Eastern Austria, Czech Republic and Western Poland

The floods of September 2024 in central and eastern Europe did not only destroy human habitats, but also temporarily restored animal habitats. Much agricultural land that was once part of river wetlands was submerged and recovered its life-supporting functionality. We tend to see and calculate the damage caused by the floods to our economies, but we overlook the red alert warning that natural disasters like these send to us about the state of our ecological systems.

This is one of the truly incomprehensible aspects of capitalism. It has created a system which directs all our attention to economic profitability, while it ignores the destruction of ecological foundations. Nobel laureate E. F. Schumacher wrote about this most dangerous dimension of capitalism: “The illusion of unlimited powers, nourished by astonishing scientific and technological achievements, has produced the concurrent illusion of having solved the problem of production. The latter illusion is based on the failure to distinguish between income and capital where this distinction matters most. Every economist and businessman is familiar with the distinction, and applies it conscientiously and with considerable subtlety to all economic affairs – except where it really matters: namely, the irreplaceable capital which man has not made, but simply found, and without which he can do nothing.”

The September 2024 floods can be understood as a lesson to be learned in systems thinking. They help us to explain the role of dominant water bodies for the regional climate. Industrial landscaping, including the regulation of rivers has turned once diverse sceneries into monotonous agricultural land. What was seen as progress, reveals itself now as destruction of the environment, biodiversity and the very foundation of our economies. How did psychologist Daniel Goleman write? In a system there are no side effects – just effects, anticipated or not. What we see as “side effects” simply reflects our flawed understanding of the system. In a complex system cause and effect may be more distant in time and space than we realize.

Northern Lapwing sightings in the Fladnitz Valley, Spring 2025

Since early September 2024 I drive our son to his new school since there is no public transportation. With a cheap 2nd hand EV, we head every morning along the Fladnitz river about 20km north. The road was blocked for a few days during the September floods, but when it opened, I have to admit that the sight of submerged fields and moving waters that ignored their industrial riverbeds did make my heart beat faster. The disaster brought a spiff of rewilding to the scenery and instead of well-tended gardens and safe roads, I felt a sense of adventure.

Most of this excitement is gone. Fire brigades dealt with the worst part of the floodings and helped affected people where necessary. And soon after, municipal road maintenance departments started to remove all evidence of a natural disaster. Along some rivers in lower Austria up to 50% of the biomass was cut back to make things look again clean and tidy. If I would have had a saying, I would have left things how they were on September 17, 2024, apart from road blocking trees and flood debris. Not only would have the sheer sight of natural destruction moved people during their spring walks and summer bike rides, but the damaged biomass would also have been a splendid habitat for different life forms.

.jpg)

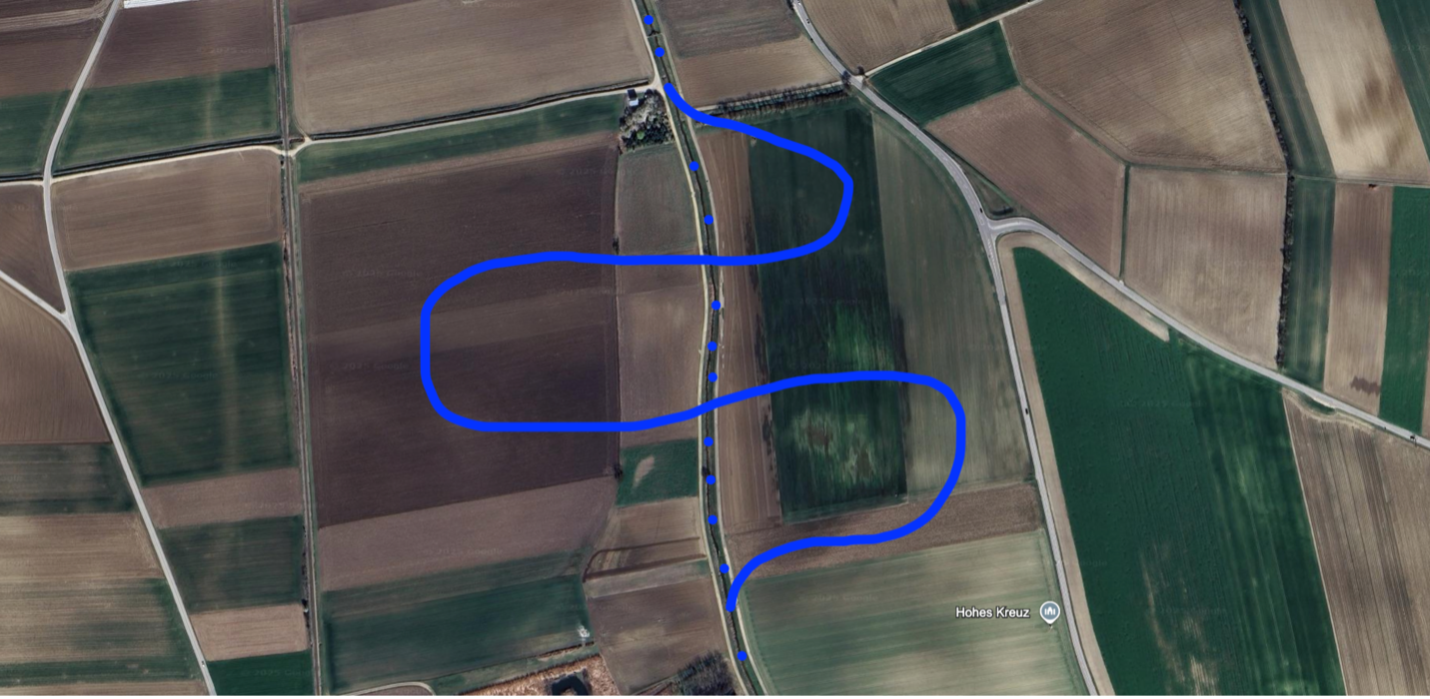

While taking our son every morning along the Fladnitz river to school, I daydreamt of a valley renaturation, with several of the flooded fields being permanently converted into a pond and the small river given ample space to meander again like it once did. Children from local school would flock to the ponds to watch birds and observe water life like it is being done in national parks. A local farmer gave my daydreams more fuel. She told me that children in the area used to be warned not to get too close to the river because the witch Salome would not only steal children, but also cattle. The story gives us an insight into how our local ecosystems have changed. In the past, the Fladnitz, like any other river, was not only a small and controlled creek, but also a marshland in which every now and then an animal drowned. The story was intended to warn children of this fate.

In another nearby village, adults are said to have believed in Salome: they scattered every year bread rolls in the fields as a sacrifice to Salome. The September floodings remind us that much farmland was originally swamps and marshy meadows that have been lost due to the industrial landscaping of the last hundred years. The result is not only a loss of biodiversity, but also a loss of culture ... stories like the one about the witch Salome are being forgotten.

In the weeks after the floods, I drove every morning along the river and often thought how beautiful this landscape would be if we could turn the flooded farmland into small and large ponds where birds could nest again, just like in Neusiedler See national park. And then one day in late February, I noticed a single grey heron, a single Great egret and a few rather unfamiliar birds displaying acrobatic flight maneuvers over one of the fields which I had imagined as a permanent lake. The next morning, I saw them again and packed my binoculars in the evening. The day after, I stopped on a dirt trail off the main road and there they were: more than a dozen Northern lapwings had chosen this field as a breeding site and their call made my heart jump! It was as if my daydreaming had been heard by Persephone.

Re-naturalization of industrial landscapes

The return of the Northern lapwing to these landscapes makes it easier to imagine healthy ecosystems which do not only provide habitat for endangered species but do also make us fall in love with the scenery which we transverse every day. It is no coincidence that alienation and acceleration coincide as sociologist Hartmut Rosa wrote. The less we are capable to care for and enjoy the environment in which we live every day, the less we will appreciate its beauty. Indeed, we turn into what is the norm for modern urbanites: we reside in one space, where many use nature as a waste dump, disposing of aluminum cans and fast-food packaging without a second thought, and if we can afford, we visit nature on the weekend in another space. We jump into our cars and go bird watching to Neusiedler See national park, because the birds which once were close to our hometowns are nowhere to be seen anymore.

I strongly believe that we can and must change this division of the environment into spaces that we urbanize and industrialize and others that we protect. Nature does not work like that. Nature is one sacred space, an interdependent entity and the human being an integral part of it. We need to start with the protection of nature, where we live and move from there in a larger and larger radius to truly pristine territories as an inspiration for how to re-design our hometowns. Humans are supposed to care for nature like a priest cares for his temple. Such is the understanding in nature-based teachings like Shintoism or Taoism, an understanding which we have lost during the axial age when the Western world became dualist and started to think about heaven and earth instead only of here and now.

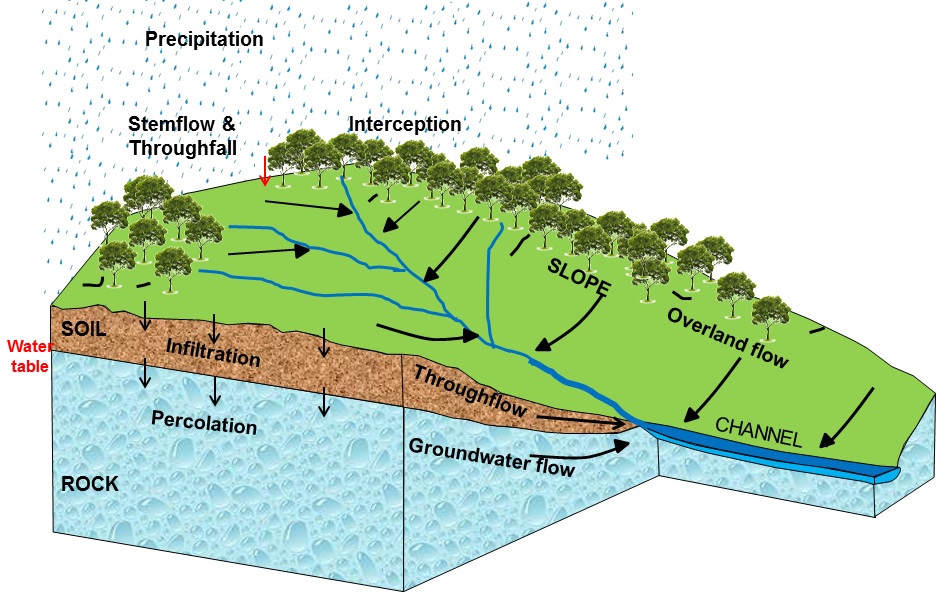

The re-naturalization of industrial landscapes turns into a question of survival, when we talk about water bodies. Falling ground water levels demonstrate all around the globe that we have damaged the water cycle and deprive land life of the water it needs to flourish. In some places, projects have started, where parts of riverbeds are built back to how they once were. One of the most basic permaculture principles is implemented on a large scale: reducing the flow of water and extending the time it remains in an area (reduce flow - increase absorption). The landscape is reclaimed to strengthen the sponge effect of the soil and groundwater levels slowly rise again. The local climate improves because the soil remains moist for longer and water is retained instead of being quickly drained away.

A practical guide to re-naturalization

When we take a field, like the one where Lapwings breed this year, and want to turn it into a permanent bird habitat, we need to conceive the idea rather like a construction projects, one that needs a basic design, a gross budget, an implementation design and a final budget. Changing landscapes from swamps to agricultural land was a huge effort a century ago and changing these fields back into swamps will be a similar if not bigger effort today. Landowners will ask, why my land and not yours? Local governments that like the idea of re-naturalization most likely will back off, when they are confronted with the required investment. The tragedy of the commons unfolds until we realize that our survival depends on the revitalization of water bodies. So, a central question is indeed, how can it be done?

This is where place-based education comes into play, a pedagogical method, which perceives students as a resource to solve real problems. David Sobel writes in his little but with wisdom throbbing book Connecting Classrooms and Communities that offering students the possibility to work on neighborhood issues is a win-win situation. Students and teachers learn through experience rather than textbooks, and communities get support in form of affordable labor. The results are not only smaller budgets for re-naturalization projects like the one discussed above, but wider community support to make them happen.

When we go into such projects with a traditional mindset, municipal departments interact with corporations and commercial offers are pitched to get contracts. Realistically speaking, parts of such projects, like excavation, earth moving, etc. which requires heavy machinery, must be implemented by suitable companies, but other parts, in particular building the infrastructure to enjoy nature, like lookout scaffoldings attached to trees or bird watching hides, which make it possible to observe wild life peacefully, are potential tinkering school projects which lower and upper secondary school students could take on, if we would reduce our liability requirements and emphasize self-responsibility.

Tinkering school is one of my favorite informal education projects. It shows that children learn best, when they have real life challenges. Tinkering school offers such experiences to a certain extent in camplike settings. Applying the tinkering school approach to hometowns and the challenges we face through climate change gives every project more urgency and integrates schools as a vital force into the long list of stakeholders and organizations that fight for ecological and social health.

Combine the tinkering school concept with the idea of upcycling as practiced by the non-profit Tanz der Teile, and you get a solid strategy of how to not only cut costs for labor and material, but also how to save GHG emissions. Instead of having to manufacture new products, available parts from within a community are used to build the infrastructure needed. Old windows from the local hospital, which had to be renovated, are not recycled, but upcycled for a bird observation shed. The wooden beams of a building which had to be removed in one part of the city is used for a bridge crossing the Fladnitz river. All these things can be done and each project is an exciting learning adventure waiting for schools to be explored and executed.

Applying a systems perspective

For some municipalities, saving money by integrating its students in ecosystem restoration measures, is only half the truth. An honest look into municipal expenditures - with a systems perspective applied - would tell decision makers that there are several ways to drive a screw into a log. Take the public middle school in the village of Furth for example. The school is located next to the Fladnitz and a short conversation with the school warden reveals the economic consequences of industrial landscaping: flooding damages in 2019 of more than EUR 400k for a destroyed heating system were then covered by the insurance. Ever since the school has no more insurance coverage, because the building is located in a "flood-prone area". The school must now self-responsibly prevent further damages and had to invest in flood resistant windows amongst other things.

From a systems perspective turning a public building into a flood resistant fortress using municipal tax money seems to be a rather unwise decision, when the restoration of the original riverbed a few kilometers upstream could not only achieve the same result, but in addition increase biodiversity by revitalizing wildlife habitats and supporting farmers by fixing a broken water cycle. Every kilometer of riverbed that is returned to its original appearance creates a small hydro-sanctuary, which helps to restore the local water cycle. Many such projects do positively influence the regional climate and help to avoid extreme events of draughts or floodings.

Further reading:

• David Sobel, Connecting Classrooms and Communities

• Womb Waters Ober-Grafendorf

• Scaling Place-Based Education through a Networked Game

• Gamified National Urban Parks – notes from a pilot project

• Synergies between the Green Steps Mobile Campus 4.0 and the Climate Frame Strategy

• Bill Plotkin, Ecological Awakening

• Tinkering school and project based curricula

• Jeremy Rifkin explaining how global warming breaks the water cycle

• Peter Wohlleben – The Secret of Trees